Anna Kataryniak Story

My name is Anna Kataryniak. Born on 17th December, 1922, in a small town called Otynia, in Ukraine. I had four brothers, Dmitro, Mykola, Vasyl and Fedir. I also had a sister, Mariya, who died at birth. We were an impoverished family. We had little clothing or shoes, poor diet, no medical facilities and winters were very harsh and cold. The result was a high mortality rate with husbands, wives and children dying prematurely. Second marriages were common.

My name is Anna Kataryniak. Born on 17th December, 1922, in a small town called Otynia, in Ukraine. I had four brothers, Dmitro, Mykola, Vasyl and Fedir. I also had a sister, Mariya, who died at birth. We were an impoverished family. We had little clothing or shoes, poor diet, no medical facilities and winters were very harsh and cold. The result was a high mortality rate with husbands, wives and children dying prematurely. Second marriages were common.

We initially lived in a small, rented house in Otynia. When I turned three, my mother moved in with her mother on a half-acre property in Molidilu Rd, three miles out of Otynia. My mother earned money by washing and cleaning for other people plus working in the fields. My father worked in town as a carpenter and visited us when he could.

Dmitro lived at home and worked on someone else’s farm during the day. Mykola was taken away as a young boy to work on a nearby farm and died at 15 from unknown causes. Vasyl moved out of home to work on a nearby farm in Sidlisdska Rd. My youngest brother, Fedir, found work as an apprentice shoemaker.

Of my siblings, I was the boldest. ‘Trouble’ was my middle name. In the yard where we lived was a small brick factory. The bricks were not kiln fired, but dried in the open. One Saturday the bricks were left outside drying in the sun over the weekend. Being a three year old, and full of mischief, I snuck out and with my fingers, I marked each brick with dog-like imprints. I didn’t realise that my antics would result in the loss of a neighbour’s family pet. When the workmen returned on Monday and saw the marked bricks, they decided to have the only dog in the area destroyed. When I questioned my parents about the death of the dog, I was told the dog was destroyed because it had ruined all the bricks. Later, I tearfully confessed to damaging the bricks but it was too late. My heart was filled with sorrow. A lesson was learnt.

At the age of four, mischief found me again. My friend Mariya and I would spend every day playing in the nearby cow paddock. My mother bought me a frilly red dress. I decided to show it off to Mariya and off to the paddock we ran, without my mother’s knowledge. When a cow saw me in my red dress, I became a target. She butted me with her horns, threw me to the ground and trampled my new dress. I was in shock and unable to shout. Mariya was able to chase the cow away. I wasn’t really hurt, until my mother punished me for ruining my new dress

At the age of four, mischief found me again. My friend Mariya and I would spend every day playing in the nearby cow paddock. My mother bought me a frilly red dress. I decided to show it off to Mariya and off to the paddock we ran, without my mother’s knowledge. When a cow saw me in my red dress, I became a target. She butted me with her horns, threw me to the ground and trampled my new dress. I was in shock and unable to shout. Mariya was able to chase the cow away. I wasn’t really hurt, until my mother punished me for ruining my new dress

One afternoon I wandered off by myself, looking for adventure. After a short time of roaming aimlessly about, I found myself lost. A woman found me and took me to my mother who was searching the neighbourhood for me. Another spanking came my way.

During summer, farmers would cart hay into town. One day, seeing a cart approaching slowly, I decided to follow it, pulling handfuls of hay as we went. I was eventually caught by my father, who in turn, passed me onto my mother for the usual spanking.

A year later we moved to the rural area where we shared a house with Grandma. Grandma had recently bought a skirt, which she washed and hung on the line. Then I came along with my scissors and cut up the skirt for dolls clothes. I didn’t even have a real doll. Just a rolled up apron. Grandma suggested to my mother that a spanking was in order. My mother bought me a new ribbon, which I also decided to cut up for my doll. After my spanking, I went outside and refused to come in and decided to stay out all night. When the light began to fade, I got scared. A neighbour’s dog, which was only let out after dark, raced past me. Terrified, I ran inside screaming, just to receive another spanking. So I decided to stay in.

Dolls played an important role in my childhood. My mother eventually bought me a plastic doll. My excitement was short-lived. A few days later, as my mother was feeding the pigs, I was holding the candle for her. Suddenly, the doll got too close to the candle and burst into flames. That’s how I lost my first doll. No, I didn’t get spanked but my mother told my father how annoyed she was putting up with my gloomy mood. He came home from work one day with a replacement doll, which I didn’t destroy. My father spent more time in town, where he worked, than at home. He’d always come home for weekends. After work my father would get drunk and often found himself in trouble which landed him in jail. With all the fighting and drinking, he gave my mother a hard life.

Dolls played an important role in my childhood. My mother eventually bought me a plastic doll. My excitement was short-lived. A few days later, as my mother was feeding the pigs, I was holding the candle for her. Suddenly, the doll got too close to the candle and burst into flames. That’s how I lost my first doll. No, I didn’t get spanked but my mother told my father how annoyed she was putting up with my gloomy mood. He came home from work one day with a replacement doll, which I didn’t destroy. My father spent more time in town, where he worked, than at home. He’d always come home for weekends. After work my father would get drunk and often found himself in trouble which landed him in jail. With all the fighting and drinking, he gave my mother a hard life.

I was eight when my father died, leaving my mother with three children. The winters were bitterly cold. My father had always provide wood and coal for the fire. Now we often went without. Life was hard without a breadwinner. When my brother, Vasyl, was a bit older he got a part-time job, which was hard to find.

In 1931 Stalin commenced his Holodomor or genocide of the Ukrainian people by starvation. From 1932 to 1933 seven million Ukrainians starved to death. At this time my family were very poor and there was not enough food to feed us all. To take some of the burden off my mother, I was sent away to work for another family at the age of 9. I spent the next 4 years in hard labour. I worked only for food and clothing. Each morning I woke at 5.00 am to take the cow to the paddock and at 11.00 am I brought her back and then had lunch. After milking the cow, I then went out in the fields for more work. At 3.00 pm I took the cow back out into the paddock until evening. After milking again, I went into the house to work and retired at about 10.00 pm.

I was always hungry and never had enough sleep. The old lady didn’t realise that a growing child needed lots of good food. When my mother came to visit, the old lady would send me outside so I was unable to tell her how I was treated, although my mother knew how I felt. The old man was good to me though, but he couldn’t make up for the way his wife treated me. During this time, I was sent to school, two miles away, for only three years but spent more time absent than attending. Most lessons were in Polish, with only 1 day a week in Ukrainian. Only the rich children could receive proper education. After three years of education, it was decided that my chores were more important than my schooling. My brothers had no formal schooling at all. As adults they received some basic schooling when the Russians took over the country.

One day I decided to run away from the farm to my mother. When I arrived she said that it would be best if I went back, as it was very hard for her to support the family. I knew she was right so I was taken back by Vasyl. When I arrived there, the old lady said that I wouldn’t have it any better elsewhere. She and the old man quarrelled constantly about the way she treated me. When she would beat me, he would interfere and another quarrel would start. After all the bickering, he decided he’d had enough and the best way out was to hang himself. Late one night he took a rope and went into the stables. He knelt down, prayed and then threw the rope over a beam. At that moment, his wife rushed in and stopped him. Shortly after that incident, she settled down a little. Although, it was short-lived and things eventually went back to the way they were.

I couldn’t take any more. Lying in bed one night, I decided to run away again. I was determined to stay awake until just before dawn but fell fast asleep almost immediately from sheer exhaustion. I woke up the next morning, which was Sunday, in time to start work. Being autumn, all the leaves had to be raked up and I knew I had a hard day ahead of me. I was up at 5.00 am and on my feet all day. For a 12 year old, the only real break I got was at lunch time. The old man and I would toil out in the sun all day, while the old lady was inside taking it easy. By tea time I was exhausted and could hardly stand.

However, this night I promised myself that I would sit up all night. I dozed off but woke up in time. I jumped out of the window and raced towards the bushes, making sure I wasn’t seen. It was very dark and I was scared. I crept through the bushes watching every shadowy outline and looking behind me the whole time. At last I reached the other side but the journey wasn’t even half over. There were houses along the way so I decided to rest beside a stable. Just before the break of dawn, I woke up and continued my journey. There were no people in sight as it was only about 4.30 am. Two more miles to go. On the other side of the village was another forest. I was terrified seeing all the creepy trees. As I hurried through the winding path, I felt as if the shadows of the trees were following me. Ahead were the ghostly trees silhouetted against the moon. The only sound I heard was the rustling of dry leaves underfoot and a little later the twittering of birds in the treetops above. Soon the glitter of daylight through the trees welcomed me to the edge of the forest. I still had to cross half a mile of fields before I came to the village where my mother lived.

However, this night I promised myself that I would sit up all night. I dozed off but woke up in time. I jumped out of the window and raced towards the bushes, making sure I wasn’t seen. It was very dark and I was scared. I crept through the bushes watching every shadowy outline and looking behind me the whole time. At last I reached the other side but the journey wasn’t even half over. There were houses along the way so I decided to rest beside a stable. Just before the break of dawn, I woke up and continued my journey. There were no people in sight as it was only about 4.30 am. Two more miles to go. On the other side of the village was another forest. I was terrified seeing all the creepy trees. As I hurried through the winding path, I felt as if the shadows of the trees were following me. Ahead were the ghostly trees silhouetted against the moon. The only sound I heard was the rustling of dry leaves underfoot and a little later the twittering of birds in the treetops above. Soon the glitter of daylight through the trees welcomed me to the edge of the forest. I still had to cross half a mile of fields before I came to the village where my mother lived.

When I reached my house, a few people were out and about. I walked around the back of the house but as Mum was still asleep, I waited on the back step for her to come out, wondering whether she would send me back again. I soon heard her making a fire in the kitchen stove before she came outside. When she saw me she rushed me inside to the warm kitchen. After telling her my story she understood how I felt and let me stay.

I spent the next year at home, during which time I worked as a housemaid for a school teacher. After the school teacher left, I unsuccessfully tried to find field work at the nearby farms to earn enough money for food. At the age of 15 I found a job in town in a small hotel, cleaning and when necessary, serving behind the counter. It wasn’t an easy job. I woke up at about 5.00 am each morning and after the hotel closed at 10.00 pm, I had to clean the rooms as well as the bar. Every morning I would go to the nearby water well and fetch 6 buckets of water. I would pay the owner for the use of his well. I worked there for 13 months.

One night in bed I suddenly heard noises downstairs and out in the street. I heard motor bikes, yelling and screaming children. When the boss came downstairs, we realised the hotel had been broken into and noticed the chairs in the bar area had been overturned, bottles smashed and many bottles of vodka missing. The boss announced that the war had begun and that the Russians were in town. Everyone was fleeing from them, for if they were to catch the rich people, they would be taken to Siberia to be imprisoned with the poor people having to work the rich people’s properties for the Russians.

The Russians put me to work in the fields of a large property. My friend, Josephine, joined me. We were later shifted to the kitchen to cook for about 50 men. After an argument with the Russian boss, I was sent out of the kitchen to a worse job. I was to milk 10 cows, 3 times a day.

One morning I woke early to start milking but I couldn’t move my arms. All my muscles ached. The pain was unbearable. Josephine dressed me and helped me downstairs. I was unable to move my fingers, so the girls helped me with the milking. I saw a doctor about my arms but he did not believe me. A few days later, the pain in my arms subsided. We were paid according to the quantity of milk obtained. It was barely enough to buy some bread. We couldn’t buy clothes as we had no money.

Early one summer morning in 1941 there was a knock at the door. It was the Russian boss. He yelled, “Get up Anna! The milking girls are already in the stables and you’re still in bed!” I had no idea of the time. When I got to the stables, the boss wanted to talk to us. He said the Germans are coming and all the young people had to flee. I asked about my mother. “I can’t just leave her.” But the older people had to stay and face an uncertain future. We were to take the cows across miles of unfamiliar country. At about 3.00 pm we rounded up most of the cows and with the boss, we started on our journey.

We walked about 3 miles to the village of our Director. On arrival we were told that our Director had fled but without him it was useless for us to continue. We were told that the Germans were approaching and the Russians had left. We could hear shooting in the distance.

We walked about 3 miles to the village of our Director. On arrival we were told that our Director had fled but without him it was useless for us to continue. We were told that the Germans were approaching and the Russians had left. We could hear shooting in the distance.

Soon somebody ventured out of the bushes. It was a Russian soldier, who told us that we couldn’t leave as we were surrounded by Germans soldiers. He told us to go back home with our cattle. So each person returned home with one cow. My mother was waiting for me. The head lady was waiting there for the boss. Everyone else had run away. Within 4 hours the Germans were approaching, burning the town by pouring kerosene over the houses, shops and stables. Sometime later we all went back towards the town in order to find food. Instead we found it burnt to the ground. Nothing was saved. The Germans took everything.

We eventually reached the city where the food was rationed. It wasn’t much. Each morning my girlfriend and I would wake up about 4.00 am and walked for two hours. We would then line up behind about 50 people and wait our turn for the daily rations. Some days there would be no food left. This went on for almost a year.

On the eve of World War II, the Kolomyia region had a population of 43,000 including a Jewish community of 19,000. It was these wealthier farmers and middle class who had provided casual employment for myself and my family. Without them survival would have been uncertain.

When the Germans came, they rounded up the entire Jewish populace and either sent them to Belzec extermination camp or shot and buried them in the forest near Sheparivtsy.

During the winter of 1942 there was an extreme food shortage in the Ukraine. This period also corresponded to an extreme labour shortage in Germany. To overcome the shortage, the Germans implemented a policy of transporting the young and healthy to Germany as forced labour. Many initially volunteered to escape the Soviet tyranny and food shortages. They were promised hot food & good working conditions. When the Ostarbeiter (OST or Eastern Workers) discovered conditions were also harsh in Germany, voluntary transfers halted and the Germans soldiers commenced rounding up able bodied persons off the street, from their homes or from churches. Some people tried to hide, but were always found. If a woman left her child at home and went to church, she would be forced to go with the soldiers and never see her child again. These people were transported to Germany to work in German factories and farms.

The last time I saw my mother was 2nd January 1942 when we were taken to the train station at Kolomyia and packed into cattle carriages. There was no room to sit or lie down. We were barely able to move. The journey took 2 sleepless days and nights, during which time we were fed only once.

Upon reaching our destination we were taken to a huge hall consisting of four walls, two windows, one door, and a cement floor. Here in these uncomfortable quarters, we spent three weeks recovering from the two gruelling days on the cattle train. My mind kept going back to my mother. I had no idea whether she survived the German invasion and if she did, she would certainly be worried about my fate. Each morning we received as much black, unsweetened tea as we wanted and one thin slice of bread. Lunch was a cup of soup and dinner was tea.

At the end of this period of detention, we were asked to choose the kind of work we wanted. I chose farm work. At the end of the process a young German lady came into the office. She beckoned me and some of my friends to accompany her. She spoke to us in German which we didn’t understand. We boarded a tram which was already full, so we had to stand for the journey. I had never seen a tram in my life and marvelled at this amazing contraption. We got off at a small village near Krefeld with the girl, who continued talking to us.

About half a mile down the road we reached a farm. The farmer’s wife (Emma) offered us a cup of tea and a slice of bread. She picked out one of the girls to work for her. She was a big, strong girl. The rest of us then continued on our way. The German girl pointed to a large farm in the distance. On arrival a very large woman of about 50 came out and asked us questions. She indicated that she wanted to know our ages. I was 20 and my friend was 40. She chose me and took me upstairs and showed me to my room. I told her my name was Anna Kataryniak and she started calling me Katarina. “No, it’s Anna.” So Katarina it was.

In the evening she laid out two large tables full of food. I thought we were having a party. I soon discovered that there were 13 other workers on the farm. When she opened the window and with a voice as loud as a hurricane yelled “Essen comen"

The first man in was Carl, who was about four ft. high and just as wide. Then came two Polish soldiers who were prisoners of war and were let out only in the day to work. One called Joseph and the other Bruno. Then followed all the other workers. As the Polish soldiers could understand German and I understood Polish, the language barrier between Emma and myself was eventually resolved.

Emma’s husband was Henry. They had a daughter, Louise, who was married to a German soldier who was killed in the war. Louise had two sons.

In two months I learnt more German than the Polish soldiers learnt in a year. I was pleased that Emma and I could converse. She was very good to me, even though I worked very hard with little sleep but there was always plenty of food. Here I worked for four years. I had every Sunday off from 1.00pm to 6.00pm. If I was out of the property after 6.00pm, I would receive a fine and after two fines, the penalty was jail. Many nights were spent in the shelter without sleep, as the Americans were bombing. This usually occurred at night but sometimes we would race for the shelter during the lunch break.

One night they bombed the nearby town resulting in many deaths and injuries. We were far enough out of town to remain safe. Our farmer, Henry, was ordered to help the survivors in town to bury the dead in the cemeteries

Our life was full of uncertainty as we were in constant danger of being bombed. At times our windows would shatter from the vibrations of the bombs. Whilst in the shelter one day our building was shaken terribly and when we ventured out we found an American plane had been shot down by the Germans and crashed on our property. The five American soldiers were dead and the workers located them and took their boots, chocolate and watches before the police came.

Our life was full of uncertainty as we were in constant danger of being bombed. At times our windows would shatter from the vibrations of the bombs. Whilst in the shelter one day our building was shaken terribly and when we ventured out we found an American plane had been shot down by the Germans and crashed on our property. The five American soldiers were dead and the workers located them and took their boots, chocolate and watches before the police came.

My brother, Vasyl, was also in Germany. He worked in a coal mine far from me. I saw him only once during the war. I wrote to him on one occasion but never received a reply. While I never saw my brother again, I did receive a letter from him eleven years later from the Ukraine.

One stormy, rainy day I looked out the window and saw a yard full of German soldiers who were fleeing from the Americans. We were told to escape in a wagon. We collected some possessions and headed towards the great bridge, about 30 miles away, which separated one part of Germany from the other. The plan was to cross the bridge before the Germans destroyed it halt the American advance. As it turned out, the Americans got there first and the blew up the bridge. Meanwhile, the Polish soldiers Joseph and Bruno had disappeared – either escaped or killed.

The Germans were now fleeing from the Americans. On 2nd April 1945, we woke in the shelter. Outside all was quiet. No planes, no bombs, just the faint sound of gunfire in the distance. All the workers had disappeared. Only the farmer’s family and I remained. We noticed that the property was full of American soldiers. When they entered the building and saw a German coat on the wall, they ordered us out and aimed their rifles at us. They thought we were hiding German soldiers. They asked who I was. I said “Ukrainian”. I assured them that there were no German soldiers here. They took my word for it but were ordered to search anyway. They were very hungry so we prepared pancakes and tea, which they enjoyed very much. We indicated to them that the cows needed milking. The soldiers then took a bucket and stool each and proceeded to milk, and I joined them. Shortly after, their commanding officer arrived in a jeep and blew his whistle. They immediately jumped to attention, tipping over half the milk supply. They explained to their commanding officer that we were Ukrainians and had provided them with a meal. They then left.

The Germans were now fleeing from the Americans. On 2nd April 1945, we woke in the shelter. Outside all was quiet. No planes, no bombs, just the faint sound of gunfire in the distance. All the workers had disappeared. Only the farmer’s family and I remained. We noticed that the property was full of American soldiers. When they entered the building and saw a German coat on the wall, they ordered us out and aimed their rifles at us. They thought we were hiding German soldiers. They asked who I was. I said “Ukrainian”. I assured them that there were no German soldiers here. They took my word for it but were ordered to search anyway. They were very hungry so we prepared pancakes and tea, which they enjoyed very much. We indicated to them that the cows needed milking. The soldiers then took a bucket and stool each and proceeded to milk, and I joined them. Shortly after, their commanding officer arrived in a jeep and blew his whistle. They immediately jumped to attention, tipping over half the milk supply. They explained to their commanding officer that we were Ukrainians and had provided them with a meal. They then left.

It was Easter Saturday, late in April. We were preparing food and Easter eggs for the next day. It was a tiring day and we all retired early. Later that night we were awoken by loud Russian voices. I could hear them destroying the kitchen downstairs and raiding the food which we prepared. Then I heard 2 shots. I was terrified and was prepared to jump out of the 1st floor window until I looked down and saw that we were surrounded by Russians. Suddenly 3 men came into my room with knives and guns. I told them who I was. They had been working in factories for the Germans during the war but as the war was over and the Germans were no longer in charge, they decided to loot German farms and collected most of our belongings. They were going to kill the German farmer and his family. I begged them not to, as they treated me very well and to everyone’s relief they were released. As the Russians left they advised me to return to my own country. The farmer and his wife thanked me for saving their lives – for the second time.

It was Easter Saturday, late in April. We were preparing food and Easter eggs for the next day. It was a tiring day and we all retired early. Later that night we were awoken by loud Russian voices. I could hear them destroying the kitchen downstairs and raiding the food which we prepared. Then I heard 2 shots. I was terrified and was prepared to jump out of the 1st floor window until I looked down and saw that we were surrounded by Russians. Suddenly 3 men came into my room with knives and guns. I told them who I was. They had been working in factories for the Germans during the war but as the war was over and the Germans were no longer in charge, they decided to loot German farms and collected most of our belongings. They were going to kill the German farmer and his family. I begged them not to, as they treated me very well and to everyone’s relief they were released. As the Russians left they advised me to return to my own country. The farmer and his wife thanked me for saving their lives – for the second time.

The Russians returned some days later, wearing clothes they stole from us. They then commandeered 3 bikes and told me once more to return home. They said that if I was still here the next time, they would force me with them. I knew that to return would mean being locked up and not see my family again.

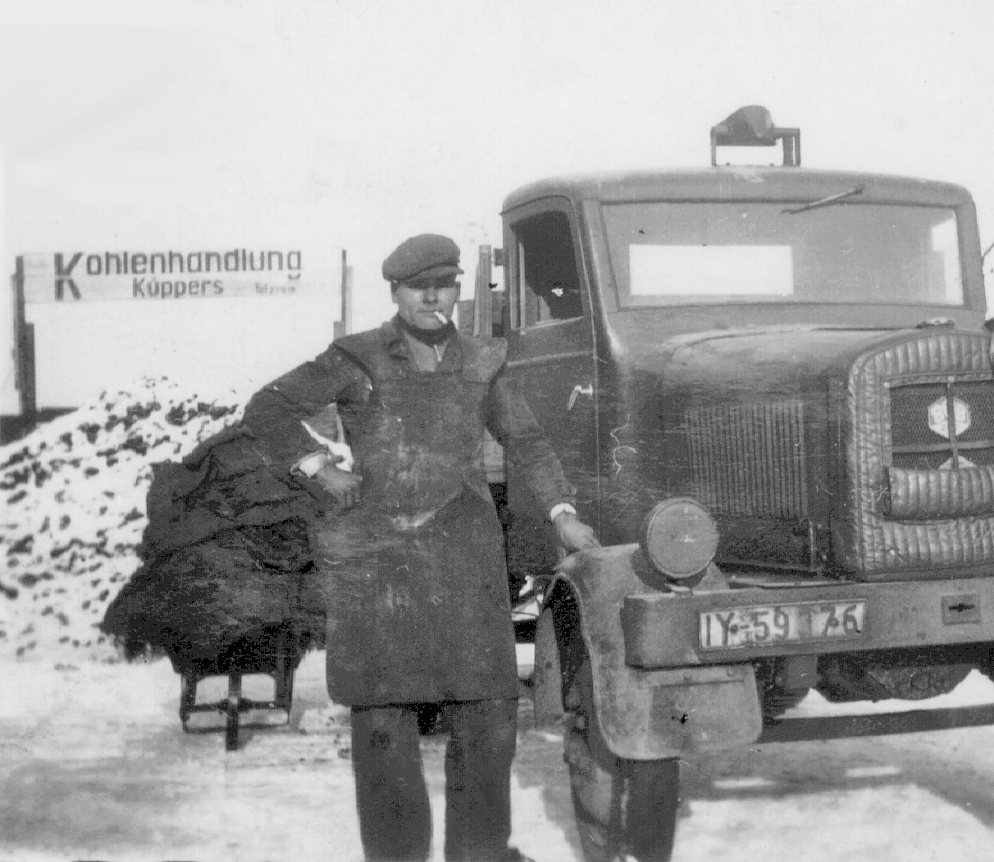

During my stay here I met Yosep Oryszczak, who worked for a coal delivery service nearby. We met only on Sundays. When I told him about the Russians’ threats, we decided to go to a nearby Displaced Persons camp where Ukrainians were staying.

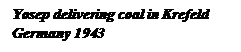

At the end of the war, we were moved to a camp in Dusseldorf. From there the Allies transferred us to a camp in Wulfrath, where Yosep and I were married and I became Anna Oryszczak. I was 23 and Yosep 29. We remained there for a year before being processed and transferred to Emmerich, where Genia was born on 5th July 1946. She was delivered by a midwife in a house. From Emmerich we were transferred to Hamburg.

We had no desire to return to the Ukraine where conditions were harsh and the Russians would seek retribution for us having worked for the Germans. The ones who were returned were often treated as traitors and sent to remote locations in the Soviet Union as forced labour. At the end of the war, the Russians expelled the entire Polish community (a third of the population) in Otynia. They were forced to leave the Ukraine and cross the border into Poland. In 1940, 41.3 million people lived in the Ukraine. By 1945 the population had dropped to 27.4 million.

In Hamburg, English officials offered us resettlement in Canada or Australia. An abundance of rabbits in Australia and the cold weather in Canada, made Australia our first choice. We left Hamburg by train and arrived in Italy a day later. We remained there for three weeks before boarding a Dutch ship, the Hansleman, for Australia. We were at last heading for the land of peace. The trip took 26 days and we arrived in Sydney on 29 November 1949.

We were located to a migrant camp in Bathurst but after three weeks, Yosep was transferred to a Quakers Hill migrant camp. From here he was collected each morning with other migrants and taken to G.E. Crane in Burwood, where he worked as a moulder. Yosep would visit by train on weekends every couple of weeks. After three months Genia and I were moved to a camp in Parkes, where I attended English classes every day.

After another three months, I was called into an office and advised that I would be relocated to Sydney to live. When I arrived in Sydney, I found that there had been a mix up with names and another family with a similar sounding name had been moved into our accommodation. Zarowski, a Ukrainian friend, permitted us to stay in their home for a few days. Meanwhile, a one room flat (originally a chicken shed) at the rear of the main house at 80 Newton Road, Blacktown was made habitable and rented for the princely sum of one pound ten shillings per week.

After another three months, I was called into an office and advised that I would be relocated to Sydney to live. When I arrived in Sydney, I found that there had been a mix up with names and another family with a similar sounding name had been moved into our accommodation. Zarowski, a Ukrainian friend, permitted us to stay in their home for a few days. Meanwhile, a one room flat (originally a chicken shed) at the rear of the main house at 80 Newton Road, Blacktown was made habitable and rented for the princely sum of one pound ten shillings per week.

I went to work at a factory in St Marys while Yosep (now known as Joseph) continued at G.E. Crane, earning 9 pounds a week. He remained with G.E. Crane for the whole of his working life. Genia was looked after by a local Ukrainian family for 1 ½ pounds a week.

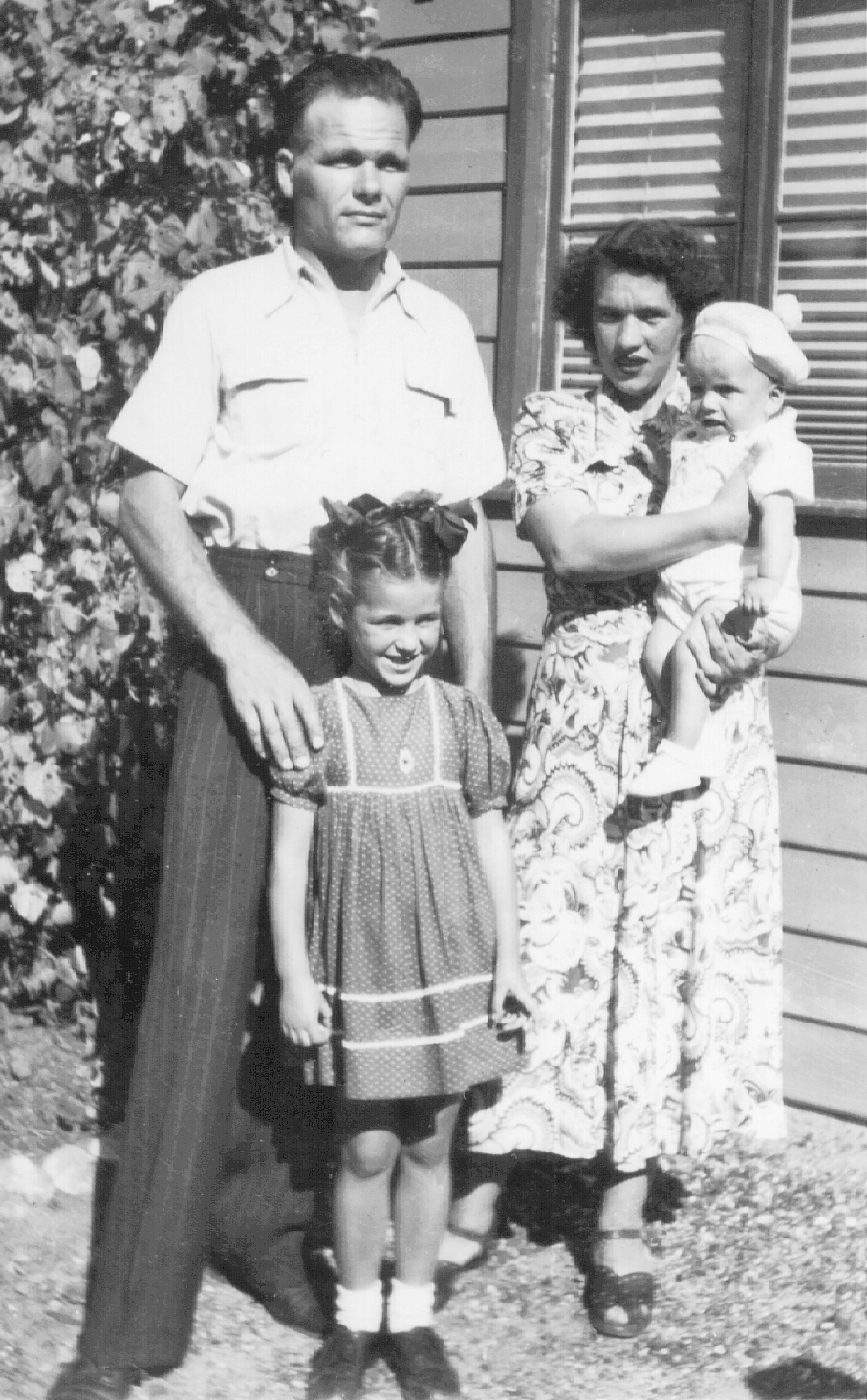

We saved Joseph’s meagre wages and a year later bought a large corner block of land at 70 Graham Street, Doonside for 100 pounds. We built a garage on the land and moved in, in 1951. Over the next two years we built a 2 ½ bedroom house on this property in which we raised our family. This home meant happiness and a secure future, free of fear and sorrow which had been missing from our lives up until then. It was our first and only real home

Yulik was born in Penrith Hospital on 5th August 1951. Joseph and I became naturalized as Australian citizens on 18th March, 1958. During the next few years, Genia became known as Jean and Yulik became known as John.

On the 16th October 1975 Joseph suffered a stroke and was no longer able to work. On 31st December 1987 and the age of 70, he suffered a massive pulmonary embolism and died in the home he loved.

Anna was now living on her own on this large property and eventually found it too difficult to cope. In April 1992 she bought a town house in Stephen St Blacktown, where she lived until she suffered a massive stroke and died 12th October 2004.

![]()